A while back I was fortunate to review Robert Wise, The Motion Pictures by J.R. Jordan, a studious filmography about Robert Wise–of course. I say of course because, yes, the title of the book is titular, but I’m also referring to the tendency of American film critics to underrate the multi-award winning director.

It’s a total snob job, quite ridiculous. Certainly Wise had some missteps, but his greatest failing, according to his critics, is something that I won’t fault him for–directing a few sequences in the Orson Welles masterpiece, The Magnificent Ambersons.

That was his job. It fell on him to do what Orson Welles would not. Either that or quit.

The Magnificent Ambersons is a landmark film despite Robert Wise’s directorial contribution, not because of it. Everybody knows that.

Regardless, the rub against Wise is that he has no signature, which is another way of saying, he has no style. And that’s the worst thing you can say about an artist.

And it’s not true. Robert Wise did have a signature…

Realism.

That’s it, if I had to sum it up in one word. And his signature of realism didn’t just manifest itself within the genre of realism–no. It’s in the precise, almost microscopic, sense of detail present in every one of his films, regardless of genre.

That Wise’s signature is subtle doesn’t mean that it is inferior.

It means it’s intelligent.

And that composition of grit and intelligence drapes the contours of noir quite nicely. In fact, I would argue that in terms of consistency, Wise’s most artful films come from noir and that his best noir, the racially hard edged, The Odds Against Tomorrow, starring a spectacular Robert Ryan and an impeccable Harry Belafonte, is unfairly overlooked when it comes to masterpieces and near masterpieces.

While Robert Wise–rightfully–would never be described as subversive, he did collaborate with subversive artists. One such artist was Harry Belafonte. Another was Abraham Polonsky.

In 1958 Belafonte was at the forefront in the intersection of looks, talent, charisma and civil rights. At considerable risk to his personal and professional security, he openly associated with Communists and Communist sympathizers within the entertainment industry who were egalitarian. As the CEO of HarBel Productions, he tapped black listed director and writer, Abraham Polonsky to write the screenplay for The Odds Against Tomorrow, while navigating the aftermath of the McCarthy investigations and participating in the modern civil rights movement.

Though jazz and noir had hooked up many times before, Belafonte literally links them with his portrayal of entertainer/musician, Johnny Ingram. The parallels and contrasts between character and performer are intriguing.

Like the character Johnny, Belafonte is a jazz enthusiast, who famously performed with Charlie Parker, Max Roach and Miles Davis. But unlike Johnny, he is not a jazz purist. Belafonte is a stage actor, musician and pop artist who could–and did–sing just about anything.

Similarly, both character and artist are nightclub entertainers though Belafonte on a grand scale and Johnny not as much. Even so, if ornamentation is an indicator, Johnny makes a nice living if not for his gambling addiction, which has torn apart his marriage, separated him from his child and put him in debt to mobsters.

Like so many criminals, Johnny does not apologize for his choices. He is bitter about them, nonetheless.

Still, we are impressed as he suavely croons and plays the Marimba in a haunting rendition of My Baby’s Not Around with Modern Jazz Quartet at the club where he is employed. We admire him as he cruises the scene in a beautiful, white, convertible Corvette and we worry about him when he is confronted by a loan shark and his unapologetically gay henchmen.

And we worry about him because he is black.

It’s 1958…so we should be worried.

Johnny’s debt (and his beautiful, white, convertible Corvette) drive him to the apartment of Burke, (Ed Begley) a corrupt, disgraced former police officer living hand to mouth because his pension has been stripped. He’s the one, Burke is, who comes up with the “perfect” heist. At the apartment Johnny crosses paths with Slater, (Robert Ryan) an aging, vehemently racist, he-man desperate for a score.

In fact, all the characters are desperate in The Odds Against Tomorrow, except one.

There is Lorry–played by a terrific Shelly Winters–who despite being astute in the business world is attracted to Slater’s tough guy magnetism. Then there is Helen, Lorry and Slater’s next door neighbor, played by Gloria Grahame. She, too, is attracted to Slater–slovenly so.

Grahame sizzles as a defiantly promiscuous woman who is turned on by violence. Never lewd, her performance evokes both interest and disgust; it is brilliant.

And finally there is the newly single Ruth, (Kim Hunter) navigating her way around the landmines of mothering and breadwinning in a racist, sexist environment. Unlike her ex-husband, she is not bitter. Instead she is determined. She doesn’t shatter when Johnny accuses her of being cold. She doesn’t apologize for being responsible.

Under Wise’s generous direction, the talented cast channels his vision of stylistic verve tempered with wincing realism, creating an atmosphere of dread. And as fine of an ensemble cast as it is, it does have a stand out.

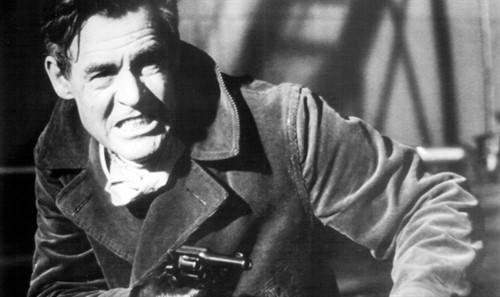

Robert Ryan.

He is scary good as Slater, a racist creep who resents the hell out of the smarter, better looking, more successful Johnny. Slater is volatile and unsophisticated. What he is not, is stupid. Consequently he understands his impulses enough to anticipate his own failures as he lurches from one disappointment to another.

As Slater, Ryan creates a memorable heavy.

For all that, where The Odds Against Tomorrow ultimately excels is in the vision of its director. Allow me to set the opening scene:

It could be a stream, the way it ripples. But it’s not…

They could be leaves carried by the rippling. They are not…

It’s rainwater collected in a gutter; the rippling caused by wind pushing trash–not leaves–up an empty street.

It’s kind of beautiful. And it shouldn’t be.

It’s art.

It’s Robert Wise.

I cannot remember how long ago I saw this film, though I suspect it will have been around 1970, perhaps at the National Film Theatre in London. I mainly remember being so impressed by Gloria Grahame. This is a film I definitely need to revisit.

Thanks, Pam.

Best wishes, Pete.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Gloria Grahame is always good. She was a wonderful actor.

–Pam

LikeLiked by 1 person

Looks really good. Anything Ed Begley is in I automatically like. Realism is a heck of a signature. This will go on our list.

Another blogger posted something about Ben Johnson in The Last Picture Show the other day… on how real he is in that movie. I’ve known people just like that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Right. The Last Picture Show is in my top 10 favorite movies. It is the ultimate ensemble cast. For me, it was Cloris Leachman that was the standout in a cast of standouts.

But, yes, Ed Begley–I didn’t say enough about him, he is terrific in Odds Against Tomorrow.

LikeLiked by 1 person

We will get it. I remember him in 12 Angry Men also.

Yea Leachman was great in that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I saw this movie many years ago. It’s for sure grim contribution to racism in the USA. I remember the last scene, when two charred corpses are to be identified and one of the policemen asks “Which of them was the white one?”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Right…I didn’t want to reveal that spoiler, because it is kind of a really strong aftershock of the climax of the film, but everybody knows where this is going in noir…it’s the process that is so fascinating.

Thanks for reading.

–Pam

LikeLiked by 1 person

I always enjoyed Robert Wise as a director,he definitely is one of the finest American directors. That said,I never heard of The Odds Against Tomorrow so I will put that one my never ending list of films to get.

Your writing is so damn good…….I feel like a pre-schooler when I look at your prose.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Stop. I appreciate the kind words, but no at your expense.

It’s right up your alley, Michael–a master director working wonderfully with a modest budget–Pam

LikeLiked by 1 person

Same here Cheetah 🙂 Btw, the replies I left under your Evil Dead blog entry has not been accepted yet and I wonder If it has something to do with WordPress? I just left a reply under your most recent blog entry and it is awaiting moderation – I say this because I love leaving comments on your wonderful blog 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Word Press is being wonky with its new editing/blogging suite. I shall see if I can fix this issue as your comments are most welcomed

LikeLiked by 1 person

The awesome tagline tell’s it like it is….

“This story that walks with a gun in it’s hand.. and slams with a fist full of fury!”

The way Robert Ryan appears in that over-saturated b&w shot. Oh my days you could feel his wrath sizzling.

Harry Belafonte’s anger shows as he fires out the vibes with his sticks and jives the cool jazz.

Damn that film is so incredible. I gave it a 9/10 but the more I’ve thought about it over the last few years I could/should bump it to a ten. It’s so good.

How about Coco the hitman with a kink! A small part but he, Richard Bright, shined (pun a little intended hehe).

So much bubbling testosterone flows through the veins of this film and the three ladies stoke the flames. Whether to make the fire rage or to simmer it down a little. Everyone, each player in the movie plays their part to perfection.

Perfection – Just like your brilliant review Pam. Absolutely fantastic.

Mikey

PS the last lines in the movie!! Uppercut to the abdomen.. POW!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Mikey. I’m glad you liked the review…the movie? What’s not to like, right? It really is a great flick. I would give it a 9…but I wouldn’t argue with a 10.

Yes…the puff enforcer…memorable. Menacing. I chalk it up to the realism factor.

So, I don’t want your review of Where Has Poor Mikey Gone? to eclipse my review. Ha!…Seriously, it’s true. So I’m going to repost your review tomorrow.

It’s the jazz tie in that I want to emphasize. That jazz noir thing. I love that.

Thanks for reading, Mikey.

–Pam

LikeLike

I’ve never seen this, great great write-up. Belafonte really was so courageous, wasn’t he?

As for Wise…. your last paragraph says it all, and boy, this in particular is beautifully stated: “It’s rainwater collected in a gutter; the rippling caused by wind pushing trash–not leaves–up an empty street.”

Wonderful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Stacey. You are too kind…Yes, Belafonte was/is wonderful. He’s still alive. In his 90s. He’s still gorgeous, too. I love him. To me he’s like the 50s Elvis…or the 1968 comeback Elvis…both of them just ooze stardom.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Pam,

I’m totally out of my league here, knowing absolutely nothing about film. But I do agree with the comment that your writing is ‘so damn good’ that I read anyway.

Btw, just today I saw a message you left on my Contact page a long time ago. I sent you an apology and will send another follow up soon.

Grace and peace to you…

dw

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great post Pam 🙂 I (like Martin Scorsese) share your sentiments about Robert Wise being an underrated director. As for Odds Against Tomorrow, I admire it more than I adore it, but it is still a very good film. In case you were wondering, for myself, admire comes close to adoration 🙂 Along with Abraham Polonsky’s thought-provoking script, the performances are electrifying from Robert Ryan, Harry Belafonte, Gloria Grahame and Kim Hunter. The use of lighting is expressive as well courtesy of it’s cinematography – not surprising considering that Wise began his directing career for Val Lewton at RKO. Anyway, keep up the great work as always 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I didn’t know Scorsese thought that about Robert Wise. Interesting…I agree, lots of things came together in the making of the film. I wanted to spotlight Dede Allen, one of the finest film editors of all time, but I had already written an overly long post so…I had to edit myself. Ha!

Thanks, as always for reading and commenting.

–Pam

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh I almost forgot Ed Begley is great too 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Solid film from the great Bob Wise. BTW, Ryan is always a great creep! LOL!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes it is. And you are right again, Ryan is always a good heavy. Thanks for reading and commenting.

LikeLiked by 1 person